Origins

BEFORE THE KORTHALS ERA AND BEY0ND. For centuries, rough-haired hunting dogs were bred in different European countries under varying names, such as Spinone in Italy, Russian Pointer in England and Smousbart in Holland. Click to Read More…

Henry IV of France used the name “Griffon” to describe his wirehaired dog in a 1596 letter. In 1683, J. E. de Selincourt, in his book Le Parfait Chasseur, described and divided pointing dogs into three groups: the Bracque (shorthaired), Spaniel and Griffon (wirehaired). The origins of the word “griffon” is likely the Latin “gryphus” (hawk), the old German “grif” (hook) and/or the French “griffe” (claw). It is difficult to say exactly what country started applying it to describe wirehaired dogs, but it has been used that way all over Europe since at least the sixteenth century.

By the middle of the nineteenth century, there were a few different versions of wirehaired dogs in Europe, including the Boulet Griffon (a rough-haired water specialist) and Guerlain Griffon (a mix between older world griffons and orange/white pointers) in France and the Stickelhaar (a mix of various wirehaired dogs, the German Setter and German Bracque) in Germany. In 1873, Eduard Karel Korthals, the son of a wealthy Dutch ammunition manufacturer, purchased four griffons of varying type in Amsterdam, moved to Germany, and began breeding his strain of griffons. Over the course of about 15 years, using carefully selective matings and ruthless culling, he turned the wirehaired pointing griffon into a uniform breed that eventually came to be known as the Korthals Griffon.

In 1877, Korthals became the kennel master for Prince Albrecht of Solms-Braunfels in Germany. The prince was one of the great sportsmen of the day. He had all manner of dogs in his large Wolfsmühle Kennel and used them on his vast hunting grounds throughout Germany (including areas that are now Poland), but his passion was English Pointers. Eduard agreed to oversee the prince’s pointer breeding program in exchange for a furnished home in which to reside and the right to use the kennel facilities to continue creating his namesake griffons. It is also thought that Albrecht shared 50% of the costs of Korthals’ breeding. It is during this time that Eduard’s Ipenwoud Kennel became well-known in Germany and abroad.

Korthals was an ardent hunter and an educated man of letters and ideas, who enjoyed sharing his passion for dogs with almost everyone. He spoke Dutch, French, German and English and was the author of many articles in these languages published in European dog magazines. His goal was to make a hunting dog for all terrains, climates and game by uniting the traits of the era’s Continental and English pointing breeds, thereby bridging the two. The continental dogs offered intelligence, robustness in all weather and terrain, a nice retrieve, and a love of water. The English dogs had better noses, more speed, further range and a spectacularly long point.

Korthals also sought a dog that maintained the look of the rough-haired continental dogs with their anatomy, robustness, medium-size, watery-repellent coarse hair and beard, and a thick downy undercoat. He eventually narrowed 23 breeding dogs down to 7 (four males and three females), which he deemed the “patriarchs”. In 1886, Korthals wrote the first breed conformation standard (see below) and in 1888, along with 140 other members, he launched the first Griffon Club, which was international in membership, yet based in Germany. Initially, it included many different types of wirehaired dogs. In 1889, after naysayers accused Korthals of mixing German Shorthairs into his line (a charge he vehemently denied), he created the Griffon Stud Book (GSB), formally deciding that only dogs able to trace their lineage directly back to these seven patriarchs could be called “pure blood Korthals.” His selection process was severe as 600 dogs were produced, but only 62 were registered in the G.S.B. In 1896, at the age of 45, Mr. Korthals, a life-long smoker, died of larynx cancer. It was 23 years after starting his Griffon breeding program, but he had already achieved broad international acclaim for his accomplishments.

Jean Castaing, writing in his book, Le Griffon d’arret, Historique, Standard, Elevage, first published in France in 1949 and widely considered to be the most important reference book on the breed, said Korthals’ dogs became famous and desirable because they had great success in field trials. (An English translation of conformation section of the fifth and most recent printing of Castaing’s book, which was retitled Le Griffon d’arret A Poil Dur Korrhals, has been included on this website.) Hegewald, the pen name of Baron von Zedlitz and the primary creator of the German Wirehaired Pointer (Deutsch Drahthaar in Germany), wrote often about Korthals’ Griffons accomplishments. Korthals and Hegewald shared a belief that most breeding decisions should be based on performance. They even worked together to create a system of field testing of versatile dogs that was ultimately used as the underlying basis of North America’s current NAVHDA system.

During Korthals life, the Griffon Club was for all wirehaired dogs, and it was agreed they could be bred together, though they could only be called Korthals Griffons if they came from the patriarchs. After his death, some breeders wanted to infuse blood from German Shorthairs and other shorthaired pointers. In 1897, Pudelpointer breeders left to form their own club. Shortly thereafter, many German breeders left to form the Deutsch Drahthaar Club. Throughout this time, the Griffon Club maintained an international membership, with succeeding presidents coming from various European countries.

Castaing wrote that “It would be a mistake to think that the improvement of the Griffon and the stabilization of its characteristics were propagated… only by using bloodlines from Korthals dogs.” In truth, after Korthals death, in addition to using dogs registered in the G.S.B., breeders across Europe began using his methods and breeding philosophy on their own wirehaired dogs. It is this unity of purpose and doctrine that allowed the breed to grow and be stabilized so quickly and definitively.

Then came the first World War (1914-1918), during which most breeding stopped. After the war ended, several countries started their own national Griffon clubs, including France and Belgium. The French started their own registry called “Livre des Origines du Griffon a Poil Dur” (LOG). It included 201 Griffons. In Germany, after WWI, the individual wirehaired breed clubs (Drahthaar, Pudelpointer, Stichelhaar and Griffon) reassembled into one club, only to be forced apart again in 1933 by Germany’s National Socialist government.

The original international Griffon Club did not survive the second world war (1939-1945). Today, around the globe, the wirehaired pointing griffon (Korthals Griffon) is represented by clubs focused solely on the breed in different countries. After WWII, the French club, Club Français du Griffon d’Arrêt a Poil Dur Korthals, took ownership of the original studbook and became the FCI parent club for the breed. It is by far the largest club with over 1000 members and it produces about 2000 pups each year.

The Wirehaired Pointing Griffon came to the United States as early as 1887, but they did not catch on broadly until after WWII. In 1951, Brigadier General Thomas DeForth Rogers formed the Wirehaired Pointing Griffon Club of America (WPGCA) with 19 other charter members. This was the precursor to today’s AKC breed club the American Wirehaired Pointing Griffon Association (AWPGA). A deeply researched and in-depth history of Wirehaired Pointing Griffons, including their North American history, was written by Joan Bailey in 1996. Her wonderful book, Griffon: Gun Dog Supreme, greatly informed this summary and is required reading for all Griffon aficionados. Another extraordinary book not to be missed is Craig Koshyk’s Pointing Dogs, Volume One: The Continentals. It is an intelligent and complete guide to versatile gundog breeds of Continental Europe.

The Korthals Griffon United States club was formed in December of 2022 as the breed’s parent club under the auspices of the United Kennel Club (UKC). Our focus is on maintaining and developing the heritage and value of the Wirehaired Pointing Griffon as a versatile hunting companion in the fair pursuit of game.

Conformation Standard

Conformation is the shape and structure of your dog. The way he is built from the ground up. It’s about the shape of different parts of his body, from his head to his tail. It’s about the structure of his legs, his paws, and his shoulders, and their relative proportions to one another. Conformation is not about what goes on inside your dog, but it has far reaching effects on those things. It directly influences functions, like speed, agility and strength. It determines predisposition to injury and level of physical abilities.

Eduard Korthals wrote our breed’s first conformation standard. Not only was he interested in recording and monitoring the appearance of his dogs, he was interested in the way his dogs performed, how fast they ran, how strong they were, how much stamina they had, etc. And, he wanted to achieve a repeatable and predictable outcome from his breeding program.

To sum up, it wasn’t evolution, or any kind of natural accident, that determined how wirehaired pointing griffons look and perform. Rather, it was Eduard Korthals who created the blueprint. We call this blueprint – our breed’s Conformation Standard.

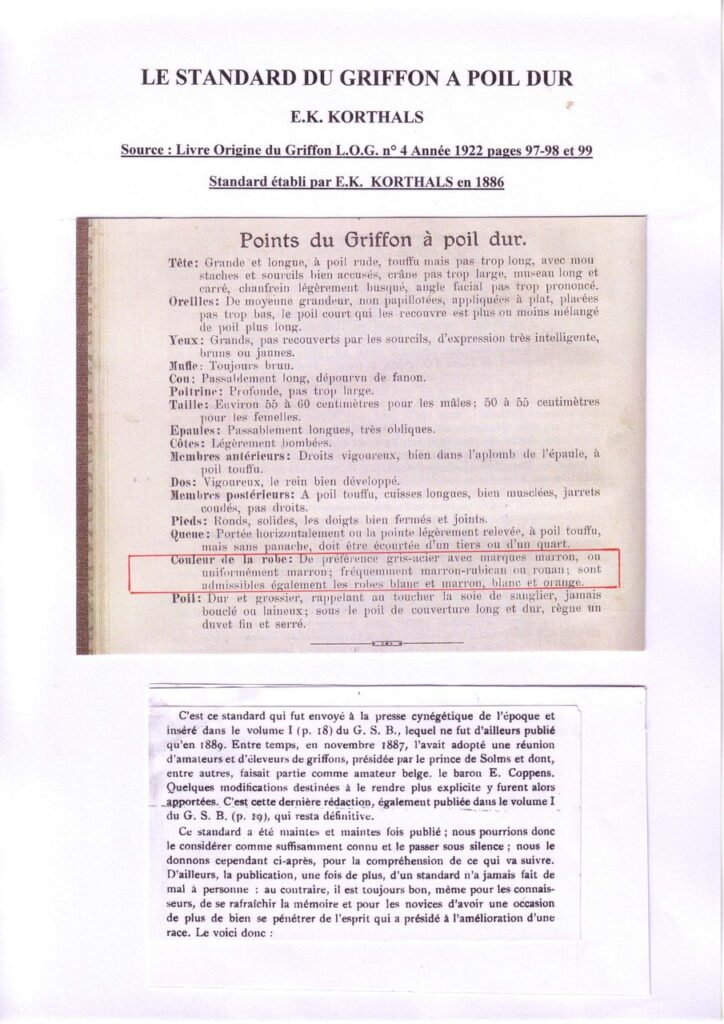

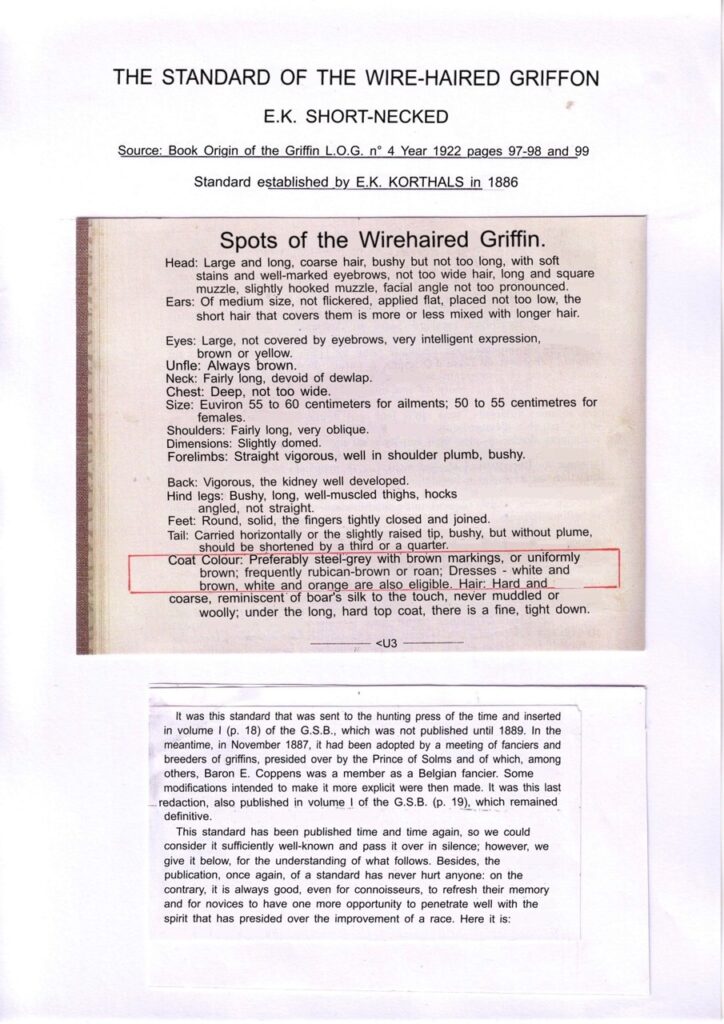

Korthals’ Original Standard – 1886

FRENCH

ENGLISH

Modern FCI Standard – 2023

It has been over 130 years since Korthals published his first conformation standard and not much has changed. The modern standard, last published by the Fédération Cynologique Internationale (FCI) in 2023 and shown below, is nearly identical. The dogs themselves would still clearly be recognized by Korthals. This is a testament to the strength of his vision, and to the fervent and ongoing efforts of the breed’s worldwide enthusiasts.

FCI-Standard N° 107 (2023) – GRIFFON D’ARRÊT À POIL DUR KORTHALS (Wirehaired Pointing Griffon Korthals). Click to read more…

TRANSLATION: Mrs. Renée Sporre Willes and Mr. Raymond Triquet. Official language (FR).

ORIGIN: France.

DATE OF PUBLICATION OF THE OFFICIAL VALID STANDARD: 01.08.2023.

UTILIZATION: Essentially a versatile pointing dog. Also used for tracking wounded large game.

FCI-CLASSIFICATION: Group 7 Pointing Dogs.

Section 1.3 Continental Pointing

Dogs, « Griffon » type. With working trial.

BRIEF HISTORICAL SUMMARY: Already mentioned by Xenophon, used as « oysel dog » widespread in the whole of Europe under different names. The breed was renewed and improved by inbreeding, selection and training without any addition of foreign blood by E.K. Korthals during the second half of the 19th century. Since, the different national clubs have remained faithful to its precepts.

GENERAL APPEARANCE: Vigorous dog, rustic of medium size. Longer than tall. The skull is not too broad. The muzzle is long and square. The eyes, dark yellow or brown are surmounted but not covered by bushy eyebrows and well developed moustaches and beard give him a characteristic expression and express firmness and assurance.

BEHAVIOUR / TEMPERAMENT: Gentle and proud, excellent hunter, very attached to his master and his territory which he guards with vigilance. Very gentle with children.

HEAD: Big and long, with harsh hair, thick but not too long; moustache, beard and eyebrows well developed.

CRANIAL REGION:

Skull: Not too broad. The upper lines of the skull and the muzzle are parallel.

Stop: Not too pronounced.

FACIAL REGION:

Nose: Always brown.

Muzzle: Long and square, of the same length as the skull, bridge of the nose slightly convex.

EYES: Dark yellow or brown, large, rounded surmounted but not covered by the eyebrows, very intelligent expression.

EARS: Of medium size, not curled inwards, flat, set on level line with the eyes, the short hair which covers them is more or less mixed with longer hairs.

NECK: Moderately long, without dewlap.

BODY: Its length is markedly greater than the height at the withers (from 1/20th to 1/10th).

Back: Strong.

Loin: Well developed.

Chest: Deep, not too wide, ribs slightly sprung.

TAIL: Carried horizontally or with the tip slightly raised, covered with thick hair but without fringing, generally should be docked by a third or a quarter. If it were not shortened, it would be carried horizontally with its tip slightly raised.

LIMBS

FOREQUARTERS:

General appearance: Straight, vigorous, with thick hair. In action, the forelegs are perfectly parallel.

Shoulder: Well set on, rather long, very oblique. Forefeet: Round, strong, toes tight and arched.

HINDQUARTERS:

General appearance: Covered with thick hair. Thighs: Long and well muscled.

Hocks : Well angulated.

Hind feet: Round, strong, toes tight and arched.

GAIT / MOVEMENT: The hunting gait is the gallop, punctuated by periods of trot. The trot is extended. Catlike movement when walking up game.

COAT

Hair: Harsh and coarse, reminding of the touch of a wild boar’s bristles. Never curly or woolly. Under the harsh top coat is a fine dense undercoat.

Colour: Preferably steel grey shade with brown (liver) patches or self-coloured brown (liver) coat. Frequently liver-roan or a close mixture of brown (liver) and white hairs. Equally permissible white and brown and white and orange coats.

SIZE: About 55 to 60 cm for males and 50 to 55 cm for females.

FAULTS : Any departure from the foregoing points should be considered a fault and the seriousness with which the fault should be regarded should be in exact proportion to its degree and its effect upon the health and welfare of the dog.

DISQUALIFYING FAULTS:

- Aggressive or overly shy dogs.

- Any dog clearly showing physical of behavioural abnormalities.

N.B.:

- Male animals should have two apparently normal testicles fully descended into the scrotum.

- Only functionally and clinically healthy dogs, with breed typical conformation should be used for breeding.

The Wirehaired Pointing Griffon – An Explanative Study of the Standard – by Jean CASTAING

Interested in knowing more about the development of our breed’s conformation standard? In 1949, Jean Castaing wrote the only known book entirely about Griffons. Many enthusiasts consider it the breed’s bible. It was originally titled Le Griffon Jarret, Historique, Standard, Elevage. It has been reprinted five times under its second title, Le Griffon d’Arret A Poil Dur Korthals. In addition to going deeply into the breed’s prehistory and history, it includes much about the breed’s conformation, which has been translated and reprinted below.

Translated from “LE GRIFFON D’ARRET A POIL DUR KORTHALS” by Jean CASTAING.

Click to Read More…

A standard must be concise, because it spans in development and phraseology; it cannot be easily retained unless it is worded in brief and precise terms. No one contests the Wirehaired Pointing Griffon standard of having this quality.

Further, a standard must be precise, so not to bring confusion and different interpretations. Concerning this subject some have reproached the Griffon standard of being somewhat vague on a few points. In truth, it is not so, but to comprehend all the true value and true significance of each of its terms, one must first know the historic evolution and the essence of the breed; one must penetrate the spirit in which the standard was written. So, more than any other, it is the result of a serious study, and the history of the breed, which permits us to trace the complete evolution and the tentative procedures of its beginnings. Because it was not written in a single day in some reunion of amateurs, and before becoming definitive and official, the text of this document passed many forms of provisionary modifications at the demand of experience and good sense parallel to the evolution of the type, until it reached its point of ultimate fixation.

Even before Korthals, many definitions of the Pointing Griffon had been given by different amateurs (Blaze 1836, Robinson 1861, Cassasoles 1863, Gayot 1867), a picture was published in the Traite des chiens de chasse (Rousellon, Paris 1827), showing us a typical Griffon not too far from the Korthalsien concept. The wiry hair differentiates him clearly from the Water Spaniel (barbet), we can find a deep chest, a long and muscular thigh. a well cleared neck, the feet hairy and well rounded, the tail docked and hairy without a tuft. The head is a little small, but we found all the characteristics of the Standard: mustache and eyebrows distinct, nonetheless without covering the eyes; the ears set high, not curled, short-haired, with a mixture of more or less long hair (this picture is reproduced in the L.O.G., vol. IV, p. 100).

The Viscount de la Neuville in 1860, and the Marquis de Cherville in l861, had also each given a definition of the Griffon as he was known in those times (refer to L.O.G., vol. IV, pp. 102- 103).

The Viscount de la Neuville clearly saw the difference between the Griffon and the barbet in La chasse au chien d’arret, 1860. He said, “The Griffon has a well-balanced frame, light and muscular, the legs are long and thin, solid and very flexible in their extremities, the coat is somewhat dense, hard, rough, long without curls, but fairly ruffled, mostly on the lower jaw, which is adorned with a thick goatee…. The head, which harmonizes itself with the rest, is more long and thin rather than spherical and adipose (fatty), and the ears are small but slightly rounded at the base. The barbet, however, is a dog with a spherical head and thick-set body, with uniform blond hair which is also woolly and curly, and which it is necessary to cut or shorten, principally around the eyes, a peculiarity that has and never will be found on a pure-bred Griffon “

With regard to the definition given by the Marquis de Cherville, it is vague and neglects principal characteristics by insisting on particular details, which have disappeared today or are considered as a fault, but he agrees that the Griffon “if he ranks among the peasants of Danube, is nonetheless no imbecile,’· and states ·’In general, the dog is tenacious, resistant, weather-resistant, courageous, and very daring and bold.”‘

In 1876, the Dutch society “Nimrod” formed a commission, in which Korthals participated, which was charged with elaborating the standards and establishing a scale of points on different breeds known in this era. The Griffon Standard naturally had its place and was accompanied by a scale of points (head and nose = 20p.; eyes and ears = 7p.; etc.) destined for judgement in expositions.

This standard began with an error which was commonly shared at that time, by Korthals as well, that “The Griffon, also called the barbet …”

Later, in 1886, a letter which was reproduced in the LO.G, vol. IV, which had been an exchange between Korthals and Boulet (who while selecting the woolly coats had a large part in the progression of the Wirehaired) on the subject of the establishment of the renovated Griffon Standard. Diverse projects of texts accompanied these letters; the following are the results of their examination:

-the confusion with the barbet disappears;

-the neck clears itself;

-the feet, large and flat, in 1876 become round;

-the chest, once large, “now becomes not too wide or too deep”, which facilitates a livelier gait involving the cantor;

-the colour black, already rare, but noticed in 1876, disappears completely;

-the presence of the undercoat, which was previously irregular, becomes obligatory; but Mr. Korthals and Mr. Boulet are not in agreement about its definition., and speak about “undercoat like the down of a duck” and then “downy undercoat”.

Furthermore, the two breeders discussed the scale of points, again in honour, notably to find out if they must give 20 points to the ribs (because they condition the structure of the chest, shoulders, etc.), or only give 2 points, which was proposed by another breeder; or they must give only 3 points for the nose because “If the nose always must be brown, why give points for it? Either the dog has a brown nose or it hasn’t; if it doesn’t have a brown nose, it’s not pure; with the scale of points, a dog whose is not brown could still win a prize as a Griffon: with this method we are going backwards.” (Letter from Korthals to Boulet, 27th of January 1886).

Therefore, after having noticed the irregularities arising from a scale of points, they were done away with.

Finally, after all these tentative procedures, a definite standard was adopted by a reunion of sixteen breeders, presided by the Prince of Solms on the 15th of November 1887. and preceded by the following protocol:

“Mr. E.-K. Korthals having, thanks to many long years of effort, succeeded in creating by selection a family of constant heredity, which known as “Griffon Korthals à poil dur” (the official name of the breed became “Griffon d’Arret à Poil Dur Korthals” (Korthals Wirehaired Pointing

Griffon) by decision on the 8th of June 1951), acquired many sympathizers in Germany, where it has been known for some time, and furthermore received public recognition by dog fanciers in other countries, notably by French fanciers, as a representative of the real type of Wirehaired Pointing Griffon. We undersigned want to make an effort to continue raising this breed while conserving its purity because of its remarkable hunting qualities and consequently believe we must deliver hereafter the characteristic points of the breed as established originally by Mr. Korthals and us, to henceforth serve as a focal point in our future breeding attempts.

The points (even though they did away with the “scale of points”, the term “points” remains) of the Wirehaired Pointing Griffon are the following:

POINTS OF THE WIREHAIRED POINTING GRIFFON

HEAD: Large, long, furnished with a harsh. but not too long, coat, with mustache and eyebrows clearly distinct, skull not too large; muzzle long and square: chamfrain slightly curved; facial angle not too pronounced.

EARS: Of medium size, not curly, lying flat but not placed too low, the short hair that covers them is more or less mixed with longer hairs.

EYES: Large, not covered by the eyebrows, very intelligent expression, yellow or brown.

NOSE: Always brown.

NECK: Relatively long, no dewlap.

CHEST: Deep chest, not too wide.

HEIGHT: Approximately 55 to 60 centimeters for adult males, 50 to 55 centimeters for females.

SHOULDERS: Relatively long, very oblique.

RIBS: Slightly rounded.

FOREQUARTERS: Straight. strong, very solid at the shoulders, bushy hair.

BACK: Strong, sturdy.

HINDQUARTERS: Bushy coat, thighs long and very muscular: hocks not straight, angulated.

FEET: Round, solid, very tight and joined at the toes.

TAIL: Carried horizontally or the tip slightly raised, with bushy hair but without a tuft, must be docked generally by l/3 or l/4.

COAT COLOUR: Preferably steel grey with chestnut (maroon) markings or all chestnut; frequently chestnut flecked with white and grey or roan. Equally admissible were coats of white and chestnut or white and orange.

COAT: Bushy and rough. at the touch reminds one of boars’ silk, never woolly or curly undercoat, fine and somewhat dense.

We are going to study successively the terms of this standard.

HEAD

SKULL: “Not too large”. It is vague. ”The head of the Griffon is not as large as the Hound or the Spaniel”, said Dhers de Save (L.O.G. vol. XIV. p. 97) but the standard also says, “head big and long”. A commentary that we must attribute to a spokesperson of the Club Français in 1926 (L.O.G., vol. VIII, p. 112) precises: skull as wide as the length (measures taken between the zygomatic arch). This then means, square, which cannot be taken for face-value, because then, the “not too large” would not be understandable; meanwhile, in his definition of the Griffon, remember earlier, the Marquis de Cherville around 1870 précised “head large and square”. To reconcile the head “large and long” on one part and the “skull not too large” on another part, all we can conclude is that the dimensions of the skull cannot be exaggerated, and especially that it cannot be larger than long. This also excluded the narrow skull which could not fit into a square, which must be avoided for another

reason: “If dog fanciers would give preference to narrow skulls,” says Mr. Paul Megnin (G.S.B., vol.

12, p. 122), “they would be entirely wrong, to reduce a skull under the normal limits could only lodge an atrophied brain and this becoming an indirect cause of the breed’s gradual lowering of its mental capacity.” In effect, experience shows that the most intelligent subjects possess a more developed skull. Finally, Mr. Paul Megnin explains clearly the apparent contradictions of the standard term with the model that he wanted to define: “It is only a simple misunderstanding,” says he, “it is not the cerebral cavity that they have (those that advocate the narrow skull), but uniquely as thou what the English call “cheeks”, the Germans call “backen” and people in France. by corruption of the language. call “parietals”. To remain true, we should simply say in French “cheeks” (joues), literal translation of the English and German terminology. In effect. it is the zygomatic that we refer to and not the parietals, which is part of the skull box. In contrary, the zygomatic is for dogs completely detached from the skull and anatomically corresponds to the cheekbones. The cheeks have no influence on the capacity of the cerebral box, nor the intelligence.

The commentary cited above (LO.G.. vol. VIII, p. 112) adds: “Skull slightly curved inward from front to back”. which signifies slightly rounded. On this rounded form of the skull, the standard is silent. Meanwhile, one of these ancestral characters of the Griffon is this slight roundness of the skull. Jourdain wrote in 1882: “The Griffon has a more rounded head … than the Hound and the

Spaniel.” The Marquis de Cherville indicates, around 1870: “The Griffon has a slightly convex head.” Questioned about this matter, Mr. Cuvelier declares: “The skull, must it be flat or round” At my advice, this latter conformation is the best, it gives more expression.”

In the book “Le chien” (The Dog), by Mr. Paul Megnin and Mr. Herout, we read, in the skull formations: Wirehaired Pointing Griffon: large and round. The “not too large” of the standard has no other objective than to avoid the exaggeration of the proportions.

As for the occipital ridge (the joining of the bones of the posterior part of the skull), it must be slightly prominent. This proceeds then from the preference that we must accord to skulls slightly rounded; the prominent occipital ridge is a characteristic of certain current dogs. On the other hand. we have noticed that an occipital ridge that usually juts out is generally accompanied by parietals that are too thick. Finally, the heads of the finest-looking Griffons of the Korthalien era were lacking this cranial exuberance.

Nevertheless, the presence of an occipital apophysis must not be, to our advice, considered as fault, if it is not exaggerated, nor must we suppose a priori (of such reasonings, deductive) a bad match, for, if we tend to believe the Marquis de Cherville, most Griffons of his era had “the head slightly convex, wide and square, terminating by a very noticeable bony protuberance.” It came evidently from the Griffons commonly seen in Franee before the Korthalsian influence.

MUZZLE: Long and square. Geometrically, a square is as long as it is wide; by specifying “long”, the standard did then mean to say that the muzzle must have a certain importance and not have a compressed aspect. The expression of the standard would not be taken in the strictest geometric sense; what must be avoided is the pointed muzzle narrowing towards the extremities. The “square” must perceive at least less of the superior face of the muzzle, that it is difficult to conceive as such of its cut and its profile, which excludes the beveled muzzle, also called pikes’ muzzle. At the same time, it must be wide, joining well with the rest of the head. This importance of the muzzle has for objective to facilitate the grasping of a prey of certain size (large hare).

The length of the muzzle must be in the same proportion as that of the skull and, so that the entire head harmonizes, the length of the muzzle must equal that of the skull. Now then, as the standard stipulates “head big and long”, we are led to believe that the whole is longer than on most other pointing dogs whose standard is silent on the subject.

The length of the whole head, from the top of the skull to the tip of the muzzle, is best at 23 centimeters. We must not fall into an exaggeration of this length, and 25 centimeters, on a male of maximum height, constitutes a limit beyond which it would be disproportionate.

CHAMFRAIN: “Slightly curved”. The chamfrain is the superior surface of the muzzle. These two words of the standard were very debated. Some do not understand this particularity. asking themselves why we had demanded this ”fault”, inconceivable on a dog which we would like to see attract a direct emanation; others, such as Mr. Bordereau, see in this particularity a probable infusion of German blood because at the time of Korthals, German dogs, Braques and Griffons had

this peculiarity. In any case, one must see a further proof of the non-infusion of Pointer blood. Mr. Bordereau shed some light on this question by publishing a letter of the 8th of April 1888, on this subject, which was addressed by Korthals to Ylr. Boulet, who was also interested in Wirehaired Pointing Griffons (L.0.G., vol. IX p. 63), the following of which are the essentials: “I thought it best to speak to the Prince of Solms before writing to you, and asking him one more time his advice on the question of “nose slightly curved”, etc., for it is he that made that remark concerning the nose. The result of our conference, as for the Prince, as well as myself, is that we by no means tend to support th.is remark, and that we are of the same opinion, that it may be better to say nothing of the nose. It is however unusual that we always spoke of the “Jewish nose” that we tried to describe; but finally, I believe, like you. that the expression of “curved nose” means something else. Finally, it is only half of the nose that is curved. At last, by saying that you are perfectly right that the nose is not curved, we are still not in agreement if it would be better to say something or not; what is your opinion?”

This letter was accompanied by a sketch of which we had no knowledge and which without a doubt disappeared; it may have prefigured the one by Professor Solars, as which there were queries on the chapter “Observations on the results” showing that the nose, said curved on the dog implicated a specific ability and manner of hunting. As said, the aforementioned letter permits, by its uncertainties, to conclude that Korthalsian Griffons must have neither the upturned nose of the Pointer, nor the nose of the Italian Hound with the accentuated base, but it is appropriate that it be horizontal for a dog serving as a connecting link between a small trotter and a fast runner, as will specify the description of the facial angle.

FACIAL ANGULATION: This is the angle of the meeting-point of the face, or stop, or still again the craniofacial angle. Not too prominent, says the standard. The average stop corresponds to the mid-line shape (P. Megnin and Herout); it is the Griffon’s form. The accentuation of this angle can denounce an infusion of Pointer blood.

So let us specify that the profile of the head must be characterized by the parallelism of the outlines of the skull and forehead (continental characteristics) or by a slight variance (open angle in the front) but never must these two lines converge in the front (Pointer).

COAT HAIR OF THE HEAD: “Rough and harsh,” says the standard, “but not too long, with mustache and eyebrows clearly distinct.” We must be clear on the words rough and harsh to understand what the hair on the head must be like.

“Rough” necessarily excludes woolly hair, which must not be found on a well-balanced Wire Haired Pointing Griffon.

Therefore, the expression “harsh” is by no means a contradiction; on the other hand, this expression implies the thickness of the coat and a certain length. This thickness is necessary as the hair of the head is intended to protect the face and the eyes against thorny bushes; a certain length is equally necessary for the same reason. But. when saying a “certain” length, we mean that it must not be an exaggerated length because, if it was, the hair would no longer be rough and would become woolly.

To have an idea of what the hair of the head must be like, says the Baron de Gingins (L.O.G., vol. XII, p. 92). you have to read the standard attentively to the end to notice that they use the same expression (rough coat) for the limbs. “If you are looking at the coat on the limbs of a Griffon showing in just proportions the overcoat (wiry) and the undercoat (woolly, fine), you will understand now through similarity in what limitations the hair of the head, and mostly of the face, must be “distinct”. ln fact. the limbs also need a particular protection for work in bush and marshland, it is the same hair as that of the face which protects them. This hair, without being soft, is not for example as rough as the hair on the back: on the other hand. it is bushier, more dense, and shorter.

Physiologically, the texture of this hair explains itself by the fact that it is an expansion of the undercoat; but it isn’t downy or woolly. as must be this undercoat on the rest of the body where a harder overcoat covers it: here, it makes of itself a thick and weather-resistant hide; it is the middle ground between wirehaired and wadding.

“The proof that the hair of the face is an expansion of the undercoat,” also says Mr. Gingins (what everybody ascertains), ”is that the German Griffon, for which above all was searched an extrawiry hair while thinning the undercoat until it completely disappeared, the beards and mustaches became even more rare than was the undercoat itself” On the contrary, a dog showing an excess of undercoat will have an excess in beard and mustache, and these will be very long and woolly; furthermore, a kind of wig will show on the skull; so the hair on the skull must be short.

The eyebrows must not cover over the eyes; if it were otherwise, in fact, they would fall over the eyes and consequently, they would be soft, not having the necessary wiriness to stay upright.

Being an expansion of the undercoat, the hair of the head, like the undercoat, is liable to have diverse and sensitive variations of growth, according to the seasons, the climate, the habitat, and the type of work. Therefore, a dog does not always have the same physiognomy, even if he has a normal undercoat. In periods of excessive growth, it is therefore necessary to proceed with a special grooming of the face.

This grooming consists of removing, by hand, the excess hairs around the ears, the eyes, and the cheeks, in a manner as to maintain for the animal his typically sculpted head. Sculpted means “the bony ledges must give an attractive overall profile” (P. Megnin and Herout); the excess hair, hair long and woolly, cannot show this profile of the head.

A Griffon with thinned beard and mustache is therefore not orthodox, since he is not protected for his duties.

Let us point out at last that from the thinness of the beard and mustache coming from a thinness of the undercoat. and the latter being the most pigmented part, we ascertain generally that it corresponds with a discoloration of the iris.

EARS

The ears of the Wirehaired Pointing Griffon have almost the same shape as that of a Pointer: flat, short, and slightly rounded; rounder, and at the same time, not as short as that of the Pointer. The earlier authors had already called attention to this particularity of the Griffon, and we must therefore not see in the shape of this ear an influence of Pointerization. We observe numerous Griffons with an ear that is too long, heavy, and sometimes curled; it is possible, as said Mr. de Kermadex, that this fault comes from some barbet ancestors.

The top of the ear must be at the same height as the eye line.

The hair covering the ears is rather short and soft, more than that of the face; it is more or less mixed with longer hairs, notably toward the bottom. This hair must not be woolly, but it is not as wiry as that of the body.

EYES

The question of the eyes is the one that raised up the most commentary. Repeatedly, the Club Français were requested to modify the standard on the colour of the iris; its committee refused to oblige, assessing that it was unsafe to modify what had been done by Korthals and his collaborators, who had their reasons, thinking it was enough to specify the meaning of the term of the standard and to rely on logic.

It is a logic that we are going to try to clarify after a brief history of the question. Let us pass along rapidly to the eyebrows, that must not cover the eyes, already examined with the hair of the head.

It is the colour of the eyes that was the most discussed. The problem is as such: the standard indicates yellow or brown, but must the complete scale of yellow be acknowledged, including straw yellow? Must we prefer all shades of yellow or shades of brown?

The answers were given by numerous zootechnicians, some sensible cynophiles, and doctrinaires referring to the texts.

The zootechnicians having dealt with the question are too numerous to cite in their entirety.

Let us limit ourselves to a resume of their thesis.

For Mr. P. Megnin and de Gingins especially, the depigmentation of the iris is equal to that of the coat. In a general matter, the latter comes from a degeneration, itself being a consequence of exaggerated consanguinity. Therefore, the clear yellow eye is a trademark of degeneration, and the dark yellow tint is of preference.

For M.A. Philipon and other earlier cynophiles, the only importance the colour of the iris has is the whim of the breeder, it has no connection with the character and the temperament and, moreover, the dark eye cannot be intended in these animals which were banished for the colour black, which is the case of the Griffon. It is to definitely eliminate the black coming from certain patriarchs that Korthals had allowed the yellow eye (L.O.G, vol. XIV, p. 99).

Mr. O’Breen replied that Mr. A. Philipon preached “pro domo” and that there is no rapport between the colour of the coat and that of the eye (white horse= brown eye, white poodle= jet-black eye); but that this is a character attached to certain species or certain breeds of which the Griffon takes place (L.O.G., vol. XIV, p. 104).

For his part, Mr. Dutillieux wrote (L.O.G., vol. IX, p. 60), “The iris of the eye with little pigmentation, after a certain number of generations, goes together with the exaggeration of the wiriness of the overcoat and the gradual atrophy of the undercoat protector of the epidermis.”

For the Baron de Gingins and others, the depigmentation of the iris goes hand in hand, for the Griffon, with the atrophy of the undercoat (German Griffons), the most pigmented of the coat and the extreme wiriness of the overcoat is the result (clear yellow eyes are more frequent on bad Griffons with a very wiry, but short, coat).

For many fanciers, the clear yellow eye is to be rejected because it often pairs up with a bad temperament and that it is, most of all, displeasing.

Among the doctrinaires, Mr. Monnot, who is one of the oldest members of the Comité du Club du Griffon à Poil dur (Committee of the Wirehaired Pointing Griffon Club), supporting the

documents, tells us, “I am absolutely convinced that the clear yellow eye is a sign of degeneration, and that it is due to the fact that the standard indicates for the colour of the eye two colours: yellow and brown. We can believe, as a matter of fact, that one of these colours is preferred over the other because in certain volumes of the G.S.B. the yellow is placed before the brown and in others, the brown before the yellow; the colour indicated first seems preferential to the secondary.”

The first list of points of the standard (18th of February 1886), gives for the colour of the eyes dunkelgelb and hellbraun von farhe, that a German would translate as ”dark yellow” and “a nice brown”.

On a second list, dated October 1897, the eyes become simply “yellow or brown”.

Now then, between the two dates mentioned above, a correspondence was exchanged between Korthals and Em. Boulet, reproduced in the L.O.G., vol. IV, under the signature of Saint Roch, out of which comes this essential matter:

-January 1, 1886, Korthals denotes “pupil brown or dark yellow”;

-the 25th of the same month, Mr. Boulet responds “pupil dark yellow or brown··;

-the 30th of the same month, Korthals draws up the plan of the standard indicating “eyes

brown or yellow”, thus rectifying Mr. Boulet’s proposition by putting the brown before the yellow.

Despite that, the standard text having never officially been modified. it is “yellow or brown” that qualifies the eyes in the G.S.B. up until 1907 (eleven volumes).

But in 1907, under the presidency of Mr. de Gingins and Mr. Prudhommeaux at the G.S.B., the latter takes back Korthals’ designation: eyes brown or yellow, and this designation was conserved until 1937, and has since without reason become again “yellow or brown”.

After the 35th exposition of Paris, in 1905, the Baron de Gingins declared, “…The French breeder has sufficiently carried his attention to the wiriness to attain in the coat, and will wisely turn his attention to the anatomical and zootechnical characteristics, such as those that I have just signaled, and which it is convenient to add the clear eye with an iris with too little pigmentation which, after a certain number of generations, progresses frequently with the exaggeration of the wiriness of the overcoat, and the result of all this is the gradual atrophy of the undercoat and epidermis.

Mr. Mannot concludes that, in the actual standard, the designation “yellow or brown” for the colour of the eyes must be replaced by “always brown”.

To back the opinion of Mr. Monnot, we can add that we can read in the judgement notes of Baron de Gingins that the “Special Exhibition of the Griffon Club of Frankfurt” in 1909:

“Pekas: I reproach him of having yellow eyes instead of hazel brown.”

“Rabot: Hazel eyes with excellent expression.”

“Rauf aus der Wettereau: … Slightly yellow eyes.” “Diana von Thuringin: Eyes sufficiently dark.”

“Zilla-Russelsheim: Hazel eyes, excellent in expression and colour.” etc.

After having resumed the essentials of these discussions, we added our own personal opinions, previously expressed in “L’Eleveur” (The Breeder) of the 22nd of October, 1933, and the L.O.G.. vol. XV, p. 113:

We argue on the question of the colour of the eyes that is required by the standard, but we always forget the two other traits which themselves, do not attribute to any uncertainties. The standard of the Wirehaired Pointing Griffon is one of the rare, if not the only (at least among those of hunting dogs), that specifies, “large eye”. By doing so, this standard of the Wirehaired Pointing Griffon wanted therefore to convey a particularity and, in effect, the eye of a Griffon ( most of the breeds of Griffons) differentiates it from that of the Pointers; it is larger, well-opened, rather round

than elliptic. Compare it to the eye of the Hound… But the standard adds, “… of very intelligent

expression”: adding that this expression must not be tough, but to the contrary, soft, trusting, and affectionate. So now show me an eye that is large, well-opened, almost round, with an intelligent expression, (and, additionally, to express softness), and that would be another colour than brown, or yellowish-brown (dark amber), (being understood that black is forbidden on a Griffon). Such an eye, if it tends toward yellow, would it be anything but an owl’s eye? In such a case, would it have this intelligent expression required by the standard. without which a Griffon would be disqualified?

And so, logic and experience corroborate that eyes that have a tendency towards brown not only express the intelligence but go hand in hand most generally with an actual intelligence more developed than on the other dogs. As for the technique that would want to associate the brown eye to the obligatory presence of black in the coat. it will be sufficient to read the standard of all Pointers on whom black is elementary to notice that, nonetheless. the brown eye (even dark amber) is the only indicated colour: Picard Spaniel. Spaniel from Pont-Audemer, French Hound, and Breton Spaniel.

If there is a theoretic relation between the colour of the iris and that of the coat, no one is contesting, when its pigmentation comes from the latter there is some kind of degeneration as noted by Mr. de Gingins and Paul Megnin. But a dog can have a light coat. even white, and be, on the other hand. very pigmented in his mucous membranes, nails, dermis, iris (P. Megnin and Herout). Alone, the absence of pigmentation is a sign of degeneration.

I myself have owned a beautiful Griffon (Ducat de la Dernade) whose coat was white, with splendid, very pigmented brown eyes.

To conclude on the question of the eyes, we shall say that the eyes of the Wirehaired Pointing Griffon must not be like those of the Hound in shape, it must have a lively and very intelligent expression. It can therefore only be brown or dark yellow. The “yellow” of the standard cannot be interpreted otherwise and to put an end to this confusion it would be desirable that the admissible yellow shade be more precise by the standard.

In a reunion of the 24th of January 1948. the Club Français du Griffon a poil dur decided to attract the attention of the judges on the importance of the shape and expression of the Griffon’s eye, and submitting our own thesis cited earlier as to what shade of the eye correlates with the shape and expression wanted by the standard, they precised, on the proposition of Mr. M.U. Fabre, president of the club, that the colour to look for is “All shades of brown”.

As for the question of the transmissibility of the colour of the eyes, its discussion drew us away from the framework of this piece of work. There has been many things written on this matter, and the question is not specific to Griffons. The laws of Mendel in the matter are sometimes kept in check by practice. Remember only, in what concerns the Griffon, is that breeders would be wise to look for sires having in their lineal ancestry a strong proportion of dark eyes, and that this particularity goes, most frequently, hand in hand with a normally abundant undercoat and a powerful head. Adding that the eye of the Wirehaired Pointing Griffon must never let show the conjunctive (the mucous membrane lining the inner surface of the eyelid and covering the front part of the eyeball) and that it must not have a globular aspect (toad eye).

MUZZLE

Always brown. This allows for no commentaries. The black truffle (nose) is eliminatory, like the presence of this colour in the coat; today it can only come from a misalliance and is very rare. Of course, the nose must not present any zone of pigmentation. This muzzle must be square and not beveled; the nostrils well opened. A split nose or double nose is a defect in all breeds, not an indication of olfactory strength, as some people may think; physiologically, in fact, this particularity cannot in any way better the sense of smell.

NECK

Relatively long. The Griffon must have the neck clear, leading to a good bearing of the head, slightly arched, not set too high or too long (swan neck, Pointers’ neck), and must not carry the head low. The photo of two couples leashed by Mr. Korthals reproduced in the G.S.B., vol. X, p. 250 clearly illustrates how must be beared the head. In fact, the axle of the neck and the bearing of the head are an indirect consequence of the axle of the radii of the chest and shoulder (on this subject, refer to the interesting plate by Mr. Philipon, p. 113 of the L.O.G., vol. XIV, and those by Mr. Megnin and Mr. Herout, Le Chien, p. 112). The Wirehaired Pointing Griffons’ neck must never, under any condition, have a dewlap.

CHEST

Deep and not too wide. The depth of the chest is in accordance, morphologically, with the length of the antero-posterior, up to the last rib; its height is the dimension of the vertical axle, taken from the withers to the breastbone (Le Chien, P. Megnin and Herout). We often confuse these two terms and we use one for the other. Here, the depth must be in accordance mainly in the sense of the height, because the more a chest is high (or descended), the more the bearing of the head will be elegant, and the deeper it is, in the sense indicated above, the more the sternum (breast-bone) will be horizontal as well as the neck, and so, the bearing of the head will be low. The chest must descend to the level of the elbow and have a sufficient length (depth) without exaggeration.

The width of the chest is its transversal diameter immediately after the shoulder; it depends on the incurvation of the ribs: so, these, on a Griffon, who is a mid-liner, are only slightly rounded; which gives rise to chest “not too large”, which means neither narrow nor tight. A chest that is too large has included elbows which are detached (exaggeration of this fault: on the Bulldog or bréviligne).

HEIGHT

The standard says: 55 to 60 centimeters for males and 50 to 55 centimeters for females. We observe a tendency towards exaggerated height, mostly on certain males. This evolution is not desirable in a time when owners look for dogs which are the least cumbersome possible. On the other hand, the Griffon cannot be shorter than the accepted minimum as seen by the standard without losing one of his most important superiorities for hunting in the marshes and the resistance to fatigue, notably in uneven terrain. The French Griffon Club’s decision on the question of tolerance in height was changed at a general meeting which was held at Mont St. Michel on June 15th, 1991. This has allowed a tolerance of not one but two centimeters more, and maintaining a tolerance of only one centimeter less. It would be desirable that the French and Belgian Clubs would come to an understanding on this subject.

SHOULDERS

Relatively long, on a slant. The length of the shoulder is in accordance from the summit of the withers up to what we call the point of the shoulder, situated at the articulation of the forearm. “The length of the shoulder favours speed” (P. Megnin and Herout, Le Chien). It is for this reason that the Wirehaired Pointing Griffons’ shoulder should be relatively long.

The shoulder is attached to the chest: the longer it is, the more it requires a large surface of attachment, that which involves therefore a chest at the same time high (see above) and of a certain length or depth. Correlating with this length, the shoulders must have an oblique position. It is this obviousness which made Mr. Megnin and Mr. Herout write, “It is ridiculous to see standards demanding a very oblique and possibly long shoulder, because an oblique shoulder is always long on a normally built dog, mid-line or longiline. The gallopers get noticed by their long and slanting shoulders, and if it happens that certain dogs with weakly-slanting shoulders possess speed, it is that they repeat their steps with greater frequency, and they make up with more frequent steps what they lose in gallops. If the shoulder is long and slanting, all the bones of the limbs will be long; the more the limbs are long, the more flexible they will be.” (Le Chien, p. 154).

If we have so made this quotation. it is because it seems to aim directly towards the Wirehaired Pointing Griffon.

RIBS

Slightly rounded. This slight roundness of the ribs conditions the width of the chest which must be moderate (see Chest paragraph).

FOREQUARTERS

: Like all normally-shaped animals, they must be straight, or should we say vertical, in order to support like pillars the weight of the body; for this same reason. they have to be sturdy. The knees must therefore be in balance. both in profile and face view. But these qualities and the contrary faults are not Griffon characteristics. so here they do not call for any particular commentaries. As for the hair which covers them, we have already mentioned it when we spoke of the hair on the head; it is a very bushy hair protecting against bushes and water: not as rough as the hair on the back, and not as woolly, it must not form a fringe in the back of the leg: this hair is shorter and denser than that of the body.

BACK

Anatomically, we differentiate the back exactly, limited in the front by the withers, to the loins, the region which follows suite, it being prolonged by the croup. The whole of these regions is commonly designated the ”top line”.

The standard only says: strong back, the loins sturdy; this excludes of course sunken backs (saddle-back dogs). the loins long and slack unsteady in action (dogs unsettled in their pace), anatomical faults not particular to Griffons.

The standard is silent on the length of the back-loin line. It would have been desirable for it to be explained, as that would maybe avoid the Griffon the tendency to evolve towards the shorter, more square type, which is that of the German Hound, the stichelharr, and the drathaar, not that of the Wirehaired Pointing Griffon. The latter, in effect, must not evolve towards the “cob” type, which is very distant from the Korthalsian Griffons. We often interpret the term of the standard “strong back, sturdy loins” as signifying a short back-loin-croup. This is completely wrong. The loin can, and must in a way, be short, but the croup must be powerful and must have a certain length, for “the length of the croup is favourable for speed.” (P. Mengin and Herout, Le Chien, p. 115). The whole top line, without ceasing to be strong and sturdy, must therefore present a certain length, for a long back favours speed. Most assuredly, there are some dogs whose form brings it closer to the square and who have speed; but these are accompanied by an irregular appearance very different from the flexible and smooth appearance, which is characteristic of the orthodox Wirehaired Pointing Griffon, who owes it to the length of his radius. to the angle of his hock, and to the length of his top line.

HINDQUARTERS

The thigh must be long and well-muscled, because it constitutes with the leg, of which the length is itself in proportion to that of the thigh, the projecting apparatus of the animal, and this latter is quite a galloper. A short leg is incompatible with the speed and extent of strides which, with less movement, enables a steady task, the maximum time with the minimum fatigue.

The question of elbowed hocks is still one of those which is a point of debate.

Some consider it a defect. It is one, morphologically, when it is exaggerated. “This special aspect to which many Griffoniers cling may have its reason: I admit that I do not see it,” said J. Dhers (L.O.G., vol. XIV, p. 98).

If the Griffoniers really cling to the elbowed hock, they have reasons: “It is certain,” said the

Baron de Gingjns (L.O.G. vol XII. p. 94) that thanks to selection, the modern Griffon is, in general, better built to work at tenacious paces than his predecessors, whose shapes were often faulty, and that straight hocks frequently prevented movement other than a slow trot.” “The hocks will be elbowed.” said for his part Mr. Dutillieux (L.O.G., vol. IX. p. 60), “which gives an easy pace, not that of a galloper, but that of a capable dog, thanks to the inclination of his radius, to sustain with ease and without heaviness. in the course of a hunting day, the search at short gallops.”

To be in accordance. and understand what the promoters of the standard wanted, it is needed, we think, one more time to appeal to logic.

So, from the beginning, what do we mean by hocks? The hock is not this inferior part of the limb which unites the leg appropriately said (currently confused with the bottom of the thigh) and the foot, the area of which the real name is ”shank”, and which is normally vertical in the perpendicular position. The hock is situated between the leg and the shank; it is the area which unites them, and it is uniquely composed of a jutting exterior, or tip of the hock, to which corresponds a hollow line on the interior. The hock is therefore an angle, or more or less, the curvature somewhat accentuated, depending on the breed. We should not, therefore, define the profile of a hock without mentioning its angle; now then, the more or less large slit of this angle depends then on the position of the limb in diverse paces (according to whether the animal sets its foot under him or behind him), and (in the normal position when the limbs are perfectly perpendicular) of the length of the leg. Compare the opening of the angle on a Poodle or the Fox Terrier on one hand and that of the Hound and the Setter on the other. So, it is understood that the standard’s expression “hocks not straight, angulated”

explains itself and is better understood, and to tell the truth, it was useless, being an obligatory consequence of the long thigh wanted by the standard. It is what the Club Français du Griffon a poil dur admitted in its meeting of the 24th of January, 1948.

Understood in another sense, the precited commentaries of Mr. Dutillieux and Mr. Prudhomrneaux would not explain themselves. Now these eminent cynophiles must know what they meant, and the Baron de Gingins says it, in another manner, by reproaching them in their judgement of dogs being “hindquarters raised higher because the posterior radius is too straight.” (G.S.B., vol. XII, p. 90). It is therefore the slant of the radius, as consequence of their length, which is to be

considered a dog, “hindquarters raised higher”, does not have this Setter shape, slightly fading, which is that of the Wirehaired Pointing Griffon. As a matter of fact. we could not understand how the shape of the hock could favour the speed, the flexibility of the pace, if it came from a particularity considered morphologically to be a fault. Many other commentaries of contemporaries and disciples of Korthals invoked, also, the necessity of elbowed hocks to favour the flexibility of the pace which gives the Korthalsian Griffon this feline gait, a sliding walk, that they share in fact with the Setters (notably the English Setters). in contrast of the jerky pace, the one-part gallop of the Poodle or Fox Terrier.

This opinion which inspires our logic of elementary observation. seems similar to the photographs of the best dogs reproduced by the volumes of the G.S.B

Nevertheless, to be exact and not to led astray those who could ascertain slanting shanks is a perfect perpendicular position, let us state in fact, this tendency proves itself on many Griffons and

other excellent dogs of midline, breeds with a long radius (Setters); so, it therefore looks normal when it is not exaggerated, and may even be looked for, because it accentuates the angle of the hock, of which we have seen the advantage. But we think that what we wanted to define is this angle, and it depends, and must depend, mostly on the length of the leg.

The hair on the thighs must be bushy and dense, by giving these terms the same sense we gave them earlier; it must never be curly, but it can present a slight wave, or rather, by staying rough (and not woolly), be slightly ruffled in contrast with the coat of the thighs of the German Griffons, always straight, very dense, and shorter, a result of an alliance with close-cropped coats. There must not be a fringe on the rump where the leg and back meet. The coat covering the shanks is much shorter, and very dense.

FEET

The characteristic of the foot of the Wirehaired Pointing Griffon is to be round (cats’ foot), in contrast with the elongated foot (hares’ foot). Technically, the cats’ foot is the same as the animals with slow and easy pace (felines), the hares’ foot being the same as the animals which pursue it (Harrier Hound, running dogs), with exception (Greyhound). The Wirehaired Pointing Griffon, in spite of the training that Korthals would make him follow at the pursuit of hares, was not meant for these functions; if we would have wanted it to hunt at a gallop, this gallop was never supposed to be that of a pack dog or a Harrier (Hound), it is a subgalloper, if we can say so, hunting at short trot and not fast pace; but this gallop must be supple, easy, and his pace, his gait must be like that of a wildcat; since we described it: feline pace. All felines have round feet.

The other indications of the standard: the toes are very tight and joined the separated toes (crushed foot) are not suitable for resistance to fatigue on rough terrain.

TAIL

At birth, the Wirehaired Pointing Griffon is born with a normally long tail. We have it docked, like most of the other continentals, for practical and aesthetic reasons:

The practical reason: hunting under cover, the dog shakes his whip-like tail with such intensity that he perceives the manifestations more strongly; in this case, he makes noise and can send the wild fowl into flight; in the bramble bush, the long whip can get skinned easily and take a long time to heal if the dog continues his service.

Aesthetic reason: the docked tail is complementary to the refined silhouette and makes the rest of the body stand out.

The tail must not be too shortened; that spoils the look of the animal. We must conform to the standard: dock one third or one quarter; the tail must not pass the height of the point of the hock. but can reach that limit. The proof that the tail must not be too shortened is that if it were best

reduced to a stump. the authors of the standard would not have indicated its horizontal or slightly raised position. As for the coat that covers it, it is of the same sort as that of the limbs. the standard using therefore the same expression “bushy hair!! All tufts are prohibited and can only be an indication of a bad match.

The docking of the tail is a very simple operation, without risk of hemorrhage, if it is done properly, shortly after birth, with scissors at the level of binding; it must be bound on the designated spot and docked. swabbed with alcohol. and the mother, by licking, will do the rest.

COLOUR OF THE COAT

The fundamental colour of the Pointing Griffon seems to be white and maroon (chestnut); it is also the primitive colour of the other continentals. But the grey shows at a very young age frequently on Griffons. The grey is theoretically formed from a mixture of white and black (or blue); but the presence of black hair and white hair is not necessary, the presence of dark pigmentation is sufficient. Amongst the patriarchs almost all were white and maroon (chestnut) or grey and maroon (chestnut); only one had a black coat (Satan); but this last one was suspected of having Pointer blood, (which explains his coat). It was to eliminate this hypothetical influence and to prevent the infusion of Pointer blood in the future that Korthals carefully eliminated all traces of black in his breeding and banished it in the standard. Actually, the apparition of black in a Wirehaired Pointing Griffon’s coat discloses incontestably a bad match; because there has never been any black in an orthodox Griffon (brought nearer to the colour of the nose).

Outside of black, all other colours are admitted; but some are preferential. The colour to look for is steel grey, not too clear, with stains of true-tint maroon (chestnut). This maroon (chestnut) can therefore fluctuate from clear chestnut to darker chestnut; but chestnut too clear going towards beige is not sought, as it indicates a depigmentation often following a generative consanguinity of a beginning of degeneration; the chestnut which is too dark, going towards black, lets us assume an alliance with the German Griffons (stichelhaar;, especially if it is accompanied by a body which is too short and clear yellow eyes.

The white was not rare, at the beginning; the volumes of the G.S.B. contain quite a few photos of Griffons of this tint, more or less mixed with chestnut spots. We also know that most subjects coming from Korthals’ kennel, or having in their veins pure Korthals blood, were more or less white. Mr. Prudhommeaux became an adversary of that colour and went even, in a sportsman-like move that showed his way of conceiving amelioration of the breed, to the point of, for a high price, buying the famous stud Zillo Hemhof, excellent trialer, in order to retire it from producing in reason of his white colour.

In an article that appeared on the Bulletin du Royal Saim-Hubert Club of Belgium in fay 1947, Mr. O’Breen points out and reproduces a Belgian lithography of 1836 representing two “white French Griffons” that seems to show that the uniformly white colour was current in the first half of the XIXth century, at least in France.

This colour still shows up once in a while today; it can come from a recall of distant blood of one of the white orthodox ancestors (observed up to the eight generation) or it can also be a sign of a beginning of degeneration by consanguinity, if it is accompanied by an insufficiently pigmented eye or mucous membrane, that is why it is considered undesirable.

In addition, the white is not to be sought because it is often accompanied by traces of orange. So, although the standard still admits white and orange, there have been questions of abolishing this coat in order to eliminate the possible influence of the Guerlain Griffons, who had a strong share of Pointer, wherein the white-orange was one of the characteristics. This colour was also current on the spinone, and this latter, as we have seen. represents certain undesirable characteristics on the Wirehaired Pointing Griffon, and so it is better to avoid it.

Finally, the unicolour chestnut coat is equally less desirable, because it generally indicates an infusion of drathaar or German Hound. As for the fiery tint, in spots or traces, it is also to be forbidden, for it also indicates a bad match which was more or less distant, probably with a ”Black and Fire” Setter or an Irish Setter.

The pups are born with a coat of white foundation with traces of maroon (chestnut). At a few weeks old, the white becomes grey, then this grey darkens more or less as the dog gets older.

The tint of the coat is subject to vary. The food, the climate, the habitat, the temperature of the country, the sea breeze or mountain air make the tint vary, even on the same dog. It seems that it is under a continental climate, but far from the sea and altitudes, that the colour best conserves its true, even tint.

COAT

The coat of a Wirehaired Pointing Griffon is complex. It has a double standard: firstly, because it is composed of two different kinds of hair, a rough overcoat and an undercoat, or flock-wool; and also because the rough coat is itself a complexity of diverse composing factors.

The overcoat is semi-long, coarse, and to the touch resembles the bristles of a boar. This point which is common with the black beast is not the only one; like the boar, the Wirehaired Pointing Griffon possesses an undercoat, and like him., is born with a bottom pale coat that changes colour with age. This similarity of character predestines the Wirehaired Pointing Griffon to work in thickets.

This comparison of the coat of the Griffon and the boar finds itself in all the descriptions of the Griffon which were made by the authors of the XIXth century previous to Korthals; but it must not however be taken to the letter, as it is not as stiff, nor as rough and coarse but, “it resembles it”, as is said by the standard, on a dog ideally coated.

Certain subjects, however, from excellent families sometimes present a fleece of soft, woolly, but rarely curly hair. Other subjects sometimes present a coat which is very rough but short (without being close-cropped). We will give the explanations of these anomalies further on.

The undercoat consists of a fine and compact down, clinging to the skin, rendering it weather-resistant in the same way as the fur of an otter and protects it from cold and bushes. On a dog that has a normal proportion of undercoat and overcoat, the flock-wool is only visible by separating the rough coat; it is more or less abundant depending on the seasons, the climate, the habitat; more abundant in winter, like the boar, it can completely disappear in summer. Combing repeatedly also removes it artificially. This flock-wool is of maroon (chestnut) colour, and very pigmented; and the presence of this proof of pigmentation or its rarity reflects itself in the pigmentation of the mucous membranes, condition of vitality, and in that of the eye, which we have seen is generally as clear as the under coat is rare. It is, in effect, exceptional to meet subjects with light eyes having an excess of undercoat. This excess of undercoat explains itself by a stifling of the overcoat; the dog gets a fleecy aspect. And the woolly hair that shows is only an expansion of the undercoat.

It is for this reason that a griffon presenting this aspect must not be declassified as a “Woolly-haired Griffon” (dog descended from the Boulet breeding) or as a barbet, if on the other hand he does not present the skeleton and the characteristics belonging to this breed, but well that of the Wirehaired Pointing Griffon. A constant grooming, combing and brushing, accompanied by “hand trimming”, generally overcomes this irregularity and restores the dog’s normal coat by airing the overcoat, which revives and grows back.

Let us remember that the hair of the head is an extension of the undercoat, rendered somewhat harsh by its direct aeration and its continual contact with the elements, and subjects possessing a thick undercoat always have nice beards and mustaches, whereas dogs with little or no undercoat have sparse beards and mustaches. In medio stat virtus.

It is this perfect balance, this even proportion of undercoat and overcoat, that is fairly difficult to obtain, and especially to maintain, in the families and the subjects. Certain critics have used this difficulty to attempt to prove that the breed has not achieved stability. This is an error, when the subjects are normally and assiduously groomed, which is generally the case of those who are presented in expositions, we ascertain (and the exceptions prove it) a large homogeneity, not counting some individual variations which have little importance. On the other hand, the irregularities aforementioned could be considered, despite the paradox, as normal.

Let us explain ourselves. A question was asked: does the wire hair have a natural origin and is it a stable characteristic? Many cynophiles and zootechnicians estimate that the wire hair does not exist at an original natural state; it would be the result of the factor of short hair and long woolly hair. The experiment conducted by the creators of the pudelpointer, the result of a union of Poodle and Pointer, seems to show it. In reality the union of the long-woolly coat (Poodle) and the short coat (Pointer or Hound) gives, at the same time, coats which are semi-long and wiry, and coats which are long and silky; the selection of the first ones gave the pudelpointer (and drathaar), a dog with semi-long, wiry coat. The Marquis de Cherville had conducted a similar experiment, by crossing Griffon and Pointer, and observed the same results. Now, in virtue of the law of separating the factors, formulated by Mendel, all forms of hybrids obtained by sexual reproduction is instable and, little by little, the reunited elements separate and return to their particularism, short haired species on one part, long-woolly coat on the other. The wire hair of the Griffon would be the result of an

ancestral union of short hair and long-woolly hair, two simple characteristics, always authenticated at the natural state: thenceforth, it would be normal to observe the apparent abnormalities mentioned above, causing the presence of short haired puppies or silky haired ones in the best of litters, as we always stated. The followers of strengthening by mix-breeding draw up and argument and maintain that to maintain the ideal coat semi-long and wiry, it is necessary to proceed with periodic infusions of short hair to families having a coat which is long-woolly.

In addition to this method presenting serious inconveniences mentioned above (see Retrempe) it does not look appropriate for this type of species. No doubt, by infusing short hair to a family affected with woolly hair, we will surely obtain wiry hair (under reservation of the modification of the skeleton and the characteristics that we have just evoked); also, without doubt, this woolly hair could it be the result of the separation of ancestral elements (genes), according to Mendel’s law: in this case the infusion of short hair will only give a temporary improvement, in virtue of the same law, and it will have to be repeated at close intervals to this cross-breeding, to maintain the breed. Now, we have seen it and it can not be seriously contested, that these frequent cross-breedings, if they maintain one character (wiry hair) forcibly destroy the others (skeleton and morale), therefore destroying the breed instead of conserving it. This is what we observed for the artificial breeds, such as the aforementioned pudelpointer.

Moreover, let us observe that the cross-breeding of short hair with woolly hair gives in one case wiry hair, in another case long, silky hair, but never directly gives woolly hair. Pierre Megnin confirms it the Marquis de Cherville himself had noticed it in his own experiences. But the silky coat is very rare on the Wirehaired Pointing Griffon, and is observed mostly on subjects having drathaar blood in their veins, which is generally confirmed by a unicolour chestnut coat. The woolly coat is much more frequent; if it came from the separation of ancestral elements, according to Mendel’s law, we would have to admit that it firstly passed through the silky form, which is observed less often. The woolly coat is less noticed at birth than after a certain age has passed, which can sometimes take a few years, by the normal aspect. Besides, Mendel’s laws must not be taken to the letter, especially when it is of domesticated breeds whose pureness is never exact and can never be proven, because the origin is partly unknown. The problem of composing elements is therefore, essentially, of an extreme complexity: it seems to be a little special to adventure oneself into this domain, in the limits of breeding which cannot be purely scientific and, one more time. sound logic proposes its solution.

That the wiry hair could be re-created in a synthetic way, like butter or petroleum, is certain but the question is not to make an experiment and create an artificial animal. Others did it. and they suffered for it. We ascertain that the wiry hair exists, and we have proof that it has been existing for a long time, since through the ages we find it mentioned. That is enough to prove to us that the wiry hair of the dog exists naturally, that it is hereditary and therefore can be conserved. If the wiry hair would not exist naturally, how could we explain the boar?

And in this controversy, it seems that we are forgetting something: what about the undercoat? The double fleece of a Griffon does not come from the match of short hair and long and woolly hair. since this match, if it produces wire-haired subjects, produces no undercoat.

Let us admit, without complicating the problem, that the double hair of the Griffon, like that

of the boar, is a natural donation and let us explain the irregularity of the woolly hair as an aspect of multiple degenerations from which no domestic animal can escape.

As for the absence of an undercoat, if it is accompanied by a wiry hair which is semi-long and normal, we can only see one other aspect of the same effect. If, on the contrary, this absence of fleece is accompanied by a coat which is extra-wiry and short, this would most likely indicate, if not for certain, the infusion of short hair.

This opinion must not, however, make us exclude completely the hypothesis of the origin of wiry hair by hybridization, and that of the separation of elements. The facts are there, in effect, which would say we are wrong: it is conceived. and always it is born. short hair in the litter. even in the best of families. and the most serious of breeders: this is proven quite a few times in the G.S.B. and the

L.O.G. We must therefore admit that at one time or another, there was a mixture of short hair; it is evident. Some see the far-off influence of a doubtful stud employed by Korthals: others admit, we have seen, that the other patriarchs themselves could very well have had blood of a short-hair running in their veins, it is possible. It is not excluded either that families have recently received recondite infusions of short-hair blood. All these hypotheses are plausible, and there is at least one which is exact. It is also exact that one of the patriarchs was a barbet; there could be other long hairs in the ascendance of a few others; more rarely in the descendants. Whatever it is, even by transforming there hypotheses into certitude, it takes nothing away from our argument: the breed that is known to us is without a doubt born of and composed both of hybrids and others which were pure. If some inherit certain hybrid elements that dissolve, it is normal, and these subjects are aberrant of birth; others are born normal, either they have inherited hybrid composite elements or simple elements from the pure ones; their eventual, future, apparent decomposition can only come from some sort of influence (lack of grooming, food, habitat, climate, function).